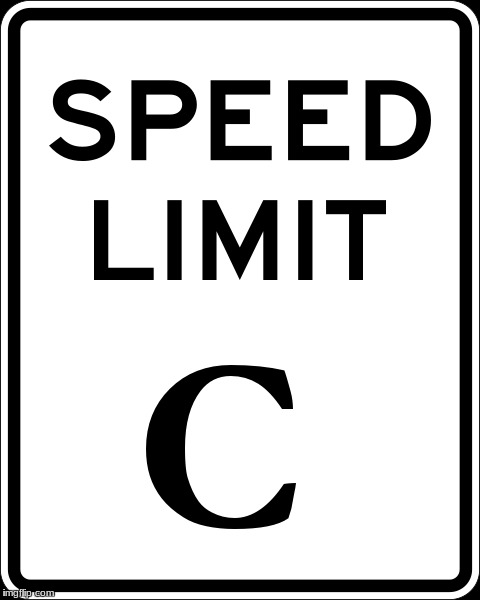

One of the key tenants of interstellar sci-fi is that you need some way to travel faster than the universal speed limit. You know, the one that's typically referred to as "the speed of light" even though we need to tag that with stuff like "in a vacuum" in order to make it actually accurate because the speed of light can actually change based on a number of external effects and it's not as if light somehow magically determines the universal speed limit, it's just that mathematically nothing in the universe can go faster than that because the laws of physics would break down if it could and light just happens to be basically the only thing capable of going that fast simply because it sorta doesn't really have mass.

I just oversimplified like six chapters of A Brief History of Time into that paragraph, so guaranteed some of it is wrong.

The point is that nothing can go faster than light via traditional propulsive means like rocket boosters or whatever, and stars are far enough apart that it's a non-trivial journey even for stuff that moves faster than light. Like hundreds of years to get to some of our most interesting neighboring systems, even at light speed. So if you want your fictional universe to take place in star systems other than the Solar System, you're going to need to make up some fictional technology that allows stuff to travel faster than light.

In my main sci-fi universe that I write there are a number of technologies that are used to circumvent the limitations of physics, and they all revolve around exiting our space-time. There's the one that lets you fly through "sub-space", the one that lets you tunnel through "sub-space", and the one that lets you take a guided tour of a parallel universe that doesn't have a fourth dimension. The idea here wasn't that there isn't another way to break the speed limit inside of our universe, but that humanity landed on the whole "sub-space" thing early on and they've just been noodling around on that idea ever since.

In a recent post I talked about how I like rules in place in a sci-fi universe to help cement a certain consistency to the whole thing. Today I'd like to discuss how I've done that, and muse on the ways I might expand the understanding of interstellar travel for my universe within those bounds.

So the question to be answered then; if traveling faster than light is impossible for ships in normal space, how do we make it so that ships can travel faster than light? The answer I went with was, simply put, that they don't travel in normal space. The physics that define the universal speed limit still apply within my sci-fi universe, but I handed them the discovery of a separate layer, distinct from but still a part of our universe, where physics fall apart. I worked backward from the idea that based on what we know now physics as we understand them break down inside the apparent horizon of a black hole, and justified that therefore black holes are essentially the doorways to that special layer of space where the universal speed limit doesn't apply.

Of course, since I can't have ships dropping black holes behind them whenever they want to use their FTL drive, I made the assumption that it was something about the Hawking radiation at the apparent horizon that made this all happen. So ships would generate a field of Hawking radiation, which would then fold the ship itself into what I lovingly refer to as Hawking space. Things in Hawking space interact with normal space-time, but distantly. Gravity is the only thing that percolates through from Hawking space to normal space (this is where a lot of "dark matter" comes from), while most things in normal space are observable from Hawking space, just wildly shifted and seemingly outside the bounds of time.

Once in Hawking space a ship can accelerate to FTL speeds and traverse interstellar distances without becoming subject to any associated time dilation. Then when they arrive at their destination, they simply deactivate the Hawking field and fold back into normal space. Navigating Hawking space presents its own difficulties, but that is in essence all that is needed for interstellar travel.

Later advances simplified the navigational component by using gravitational control in concert with a Hawking field to form a sort of tunnel through Hawking space that people called a worm hole in homage to Carl Sagan. Using this galactic wormhole drive a ship will essentially carry a small pocket of normal spacetime through a tunnel in Hawking space, allowing them to avoid both the difficulties of navigation and the effects of time dilation.

This explanation works well enough for my purposes. It presents interesting design problems where ships that have FTL drives need to produce massive amounts of power and house a large apparatus for generating an extensive artificial gravitational field and an accompanying Hawking field of sufficient size. There is another method of FTL travel called bending, which consists of genetically engineered humans folding themselves and anything they can touch through another dimension with no time, allowing them effectively instantaneous travel through space to return to our dimension at another point. That method presents more societal challenges than design challenges, and is the mode I reach for when I really need something that serves the plot rather than the science.

So as far as Humanity understands, that's how you travel faster than light. It's powerful too, with enough energy and enough raw material you can use these Hawking space tunnels to move artificial constructs almost planetary in scale. As such, most research into other methods of FTL has been abandoned in favor of making the wormhole drive more efficient. But I haven't given up on hypothesizing other methods of FTL travel for use by other, non human societies.

I like the idea that you could broadcast something like a coherent beam of photons that are quantum-entangled to some large installation on a planet years ahead of when you want to travel, and then once the blast of light reaches the location you want, you can swap places with the beam, carrying the quantum-locked light, the surrounding gravity well, and anything inside of it to the location of the beam and leaving nothing behind but a flash and suddenly empty space. Does it make sense? Not much. But would it be called "dark jumping" and does that sound super cool? Heck yes.

I also like the supposition that for smaller vessels you could sort of infuse a Hawking field into the matter of the ship itself, allowing it to exist sort of simultaneously inside Hawking space and normal space. This would allow it to defy the laws of physics while still presenting itself in normal space time, and that shiz would look scary as crap to anyone that happened to observe it.

All of these are musings on answering the simple question of "how do they travel between stars?" I've found that if you're writing sci-fi answering that question concretely is going to present you with far more interesting and rewarding story possibilities than not answering it, and it'll make your universe feel that much more real.

Comments

Post a Comment